Ruinas de Ujarrás, Ujarrás, Cartago, Costa

Rica

Photo

by Jonathan Acuña (2018)

Business

Understanding

The first

stage of Data Science

By Prof. Jonathan Acuña-Solano, M. Ed.

|

|

Head

of Curriculum Development

Academic

Department

Centro

Cultural Costarricense-Norteamericano

|

Senior Language Professor

School of English

Faculty

of Social Sciences

Universidad

Latina de Costa Rica

|

|

Post 338 / DS Log 7

|

|

Data Science is quite peculiar when it

comes to the steps one has to follow in order to start the process of

comprehending what exactly needs to be addressed when a company’s problem needs

to be explored, understood, and then resolved. But why is it so essential to

establish the “business understanding” at the start of the Data Science

methodology? Let’s explore some potential answers to this question especially

when linked to a very specific problem.

“Business understanding is the first stage of the data science methodology; it provides clarity about the problem to be solved and the data that should be used”

Business Problem Sample:

|

|

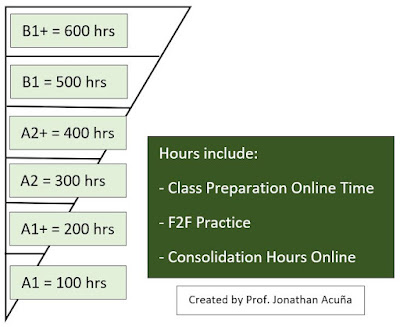

A language school whose

students are not obtaining the expected CEFR outcome at the end of its

program

|

|

2)

Understanding how the school is being affected by a poor performance of their

graduating students will help stakehoders to formulate the right question(s)

to ask to set the data requirements to gather information.

|

3)

This open and sincere discussion with the school academic stakeholders will

provide room to comprehend why the problem needs to be given a solution, the

reasons why the current state of affairs has to be amended.

|

“To establish business understanding,

structured discussions with different stakeholders must happen so that the

research focus (goals and objectives) can be classified” (Laureate Education Inc., 2018) . It is crucial to

clarify at this point that these “discussions” cannot just be held to ask

company contributors what they want in terms of the enterprise’s problem;

consultations have to be organized to get to the gist of the research focus

needed to find solutions to the problem. Team members must come from different

areas in a company; business understanding cannot just be provided by one single

individual. And through all these deliberations goals and objectives also need

to be clearly stated in the minds of company’s stakeholders and the data

scientist(s). Forgetting this simple step in business understanding may trigger

the wrong results.

Business Problem Sample:

|

|

A language school whose

students are not obtaining the expected CEFR outcome at the end of its

program

|

|

2) The

group of academic contributors must come from different areas of the

department. This is not just about an academic director’s perception; it has to

come from all areas that constituted the department.

|

3) All

members of the academic team must have clearly stated -in their mind- the

goals and objectives of finding the reasons why students are not achieving

the correct CEFR level. Everyone has to embrace the project.

|

“Once a business understanding is in place, key business partners can remain engaged and provide support and guidance to project members”

Business Problem Sample:

|

1) Though

there are structured conversations among the academic stakeholders, they need

to remain part of the project and not just stay aside and wait for results.

These people help in discovering solutions.

|

A language school whose

students are not obtaining the expected CEFR outcome at the end of its

program

|

|

2) Academic

collaborators support the data scientist(s) when they contribute with

information to consolidate the business understanding here linked to the poor

CEFR performance of the school’s language learners.

|

3) Academic

engagement will be present all across the process since as team players, they

can provide the data science group with guidance especially when a piece of

the puzzle is missing in its right position.

|

As a first stage in Data Science,

business understanding is decisive and imperative. Lack of understanding among

all participants in a data science team can lead to formulating wrong questions

and obtaining inaccurate answers. In the example used in this presentation of

facts associated to the language school, there are plenty of people involved in

the search for an answer as to why their learners are not achieving the mastery

of the CEFR level the program aims at. Their participation in the process to

find answers to the questions they pose as central will determine the goals,

objectives, and scope of the possible answers they can obtain. As stakeholders

they can make better decisions in regards to what needs to me done to help

their students become competent English speakers.

References

Laureate Education Inc. (2018). Asking Questions

with Data Science. Retrieved from One Faculty: https://dtl.laureate.net/webapps/blackboard/content/listContent.jsp?course_id=_165016_1&content_id=_801203_1&mode=reset

Post 338 - Business Understanding by Jonathan Acuña on Scribd

Sunday, August 18, 2019