My 3rd

Lesson Learned at ABLA 2016:

“English Proficiency and the Common European

Framework”

By Prof. Jonathan Acuña-Solano, M. Ed.

School of English

Faculty of Social Sciences

Universidad Latina de Costa Rica

Wednesday, August 31, 2016

Post 287

“English has grown so much in recent

decades that it is commonly used among millions of people who did not learn it

as their first language” (Escobar, 2016) . And because of this amount of

non-native speakers, the Common European Framework of Reference (commonly known

as CEF) was born in November 2001 to deal with what learners were really able

to do along their contrasting developmental phases. Still educative

institutions, such as language centers or schools, have not been able to

comprehend the real scope of what the CEF is meant in terms of learner language

development. Is CEF still unclear for ELT professionals and for academic

decision-makers?

Escobar (2016), during the ABLA 2016

convention in Houston, posits the issue concerning the misinterpretation of the

CEF by asking the following: “Is the concept of a ‘native speaker’ still useful

in light of the transformations that English has experienced in its expansion?”

Based on my experience with curriculum development and instructional design,

publishers’ statements regarding their English language series in which a

student can cover a book of theirs in 90-120 hrs of instruction is a

teaching/learning fallacy. It has been roughly claimed by CEF standards

developers that to move from one level to another, some 200 hrs of instruction

are needed. And then what it is also misinterpreted by professionals is that A1

means someone who has never studied English in his/her life. But the fact that

a good amount of student inter-language is needed to achieve an A1 CEF level.

Based

on the British Council (Wright, M., n.d.) , an A1 – breakthrough or beginner can

be described as someone who …

· Can

understand and use familiar everyday expressions and very basic phrases

aimed at the satisfaction of needs of a concrete type,

·

Can

introduce him/herself and others and can ask and answer questions about

personal details such as where he/she lives, people he/she knows and

things he/she has, and

· Can interact

in a simple way provided the other person talks slowly and clearly and is

prepared to help.

But, could an A1 really do this in less than 200 hrs of

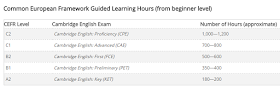

instructor-led work in class? And by paying attention to Desveaux (2016) in the Cambridge English Support Site

(see chart below), it looks like a learner in a CEF Level A2 has already

undergone a minimum of 180 hrs. But what about an A1? Did this learner manage to complete his/her learning, the one stated by the British Council, in just 20

hrs of class instruction? These numbers do need revision since we language

teachers know that these hours become volatile and fallacious when we listen to

our students trying to communicate in the target language.

Click picture to make it larger.

Another

issue that is nebulous when one is trying to “digest” it is whether online

hours do count or not. When I asked Escobar during his talk at the ABLA 2016

convention, he insisted that these hours

count as long as they are instructor-led. Basically, these hours on an

online platform in a hybrid or blended learning format can be taken as part of

the hours needed to complete a CEF level. As Dr. Glick (2016) also stated in his ABLA 2016 presentation while explaining this

case study in a Mexican university, online/blended hours have a positive impact

on language learning. And though all this sounds wonderful, do these online

hours count when they are not “exactly” guided by the instructor and a platform

is just used as an online workbook? And how much do these rather “unguided

hours” impact language performance? Up to this point, this is unquantifiable!

Perhaps as my curriculum partner, Luis Quesada (from CCCN in Costa Rica),

suggests, we should divide these hours into two since he believes that these

hours may have some positive impact in the development of student English

interlanguage.

Federico Escobar,

College Board, San Juan, Puerto Rico, USA

At this point of the discussion, I want to go back to one of

the most striking ideas presented by Escobar in his talk, “How should we

measure the effective use of English as a lingua franca?” (2016). Escobar is

giving a different direction in the real understanding of language performance

of English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) since CEF descriptors only refer to what a

learner is able to do in the various levels the scale has and not what native

speakers are meant to do depending on their use of their first language. By

bumping into this misinterpretation “lump,” CEF does not need to be re-defined

but correctly understood. Descriptors are clear enough to have us comprehend

that learners today are using English as a lingua franca due to their

interactions with other non-native speakers of the target language. English is

not being learned to talk to native speakers but to improve the learner’s

chances of being employed. To sum up, CEF is not about native-like language use

and performance, it is about, as Escobar (2016) explained in his talk, the

interlanguage students develop along the many phases the CEF encases in its

scale and how it is used to interact with other EFL speakers.

Some other

additional reflections Escobar’s talk triggered in my mind after the ABLA

convention are connected to the way we run language programs in our binational

centers. Courses cannot be created around publishers’ statements of their

language series since they are not down to earth in the projection of hours

needed to climb the CEF scale ladder. A student cannot move up in the CEF scale

in 90 to 120 hours; more hours of instructor-led time are needed to develop a

given level. As explained by Escobar (2016), this is the reason why the CEF now

includes A1 and A1+, A2 and A2+, and so on, because in ELF learner language

development cannot be encased in hours but on what students can do based on the

CEF descriptors of language mastery. It is for this reason that the binational

centers’ roles, as well as the one by any serious

language school, is to educate their teachers to administrate this tool

correctly and to not expect native-like language production from their

students. Additionally, language centers need to instruct their learners that

they are not meant to expect to speak like a native speaker when speaking but

to anticipate some native-like production from time to time. Most of the time

the what it is going to be witnessed by the instructor is the development and

polishing of student ELF interlanguage.

Finally,

online work in blended or hybrid formats do count if these hours are truly

guided by the instructor. Online work per

se cannot be quantified as part of instructor-led hours spent by a sudent

on the school platform, or language series platform. A platform is not supposed

to be used by the teachers as an online workbook; it needs to be connected to

the course continuum to become meaningful for the student (inter) language

development.

References

Desveaux, S.

(2016, August 5). Guided learning hours. Retrieved from Cambridge

English Support Site:

https://support.cambridgeenglish.org/hc/en-gb/articles/202838506-Guided-learning-hours

Escobar, F. (16-19 de August de 2016).

English

Proficiency and the Common European Framework. 21st Century Challenges ABLA 2016 Convention Program . Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico: Insituto Mexicano

Norteamericano de Relaciones Culturales.

Glick, D. (2016, August 16-19). Maximizing Learning Outcomes

through Blended Learning: What Research Shows. 21st Century Challenges ABLA 2016 Convention Program . Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico: Instituto Mexicano

Norteamericano de Relaciones Culturales.

Wright, M. (n.d.). Our levels and the CEFR.

Retrieved from British Council Portugal:

https://www.britishcouncil.pt/en/our-levels-and-cefr